Making Sense of Grief in Storytelling

Por José Luis Lobera • 21/11/2025 • Comunicación

One of the most challenging emotional states to bring into our stories is the grief we experience after losing a loved one. That blend of sadness and emptiness —sometimes tinged with helplessness or anger— can be difficult to capture on the page.

When we are telling a story that unfolds over a longer period of time, it becomes even more complex to show how sorrow can gradually evolve into acceptance. In a recent social media post, Spanish psychiatrist Marian Rojas put it this way: “With time, pain stops being an open wound and becomes an invisible bond that connects us, from another place, with the person we loved.”

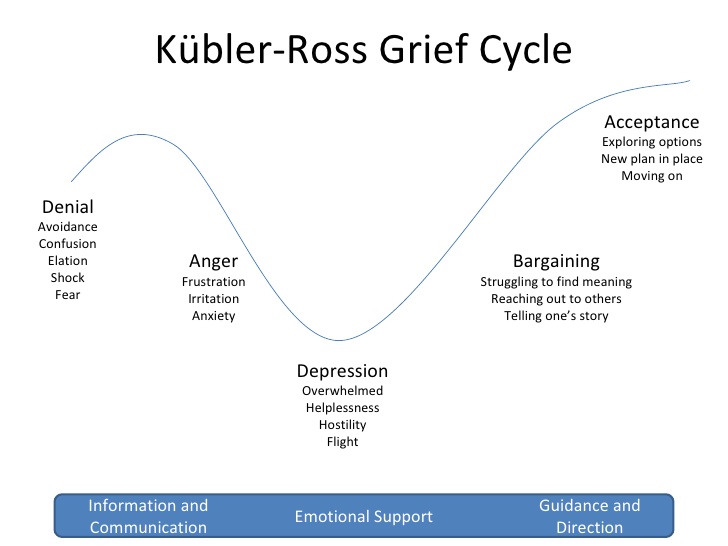

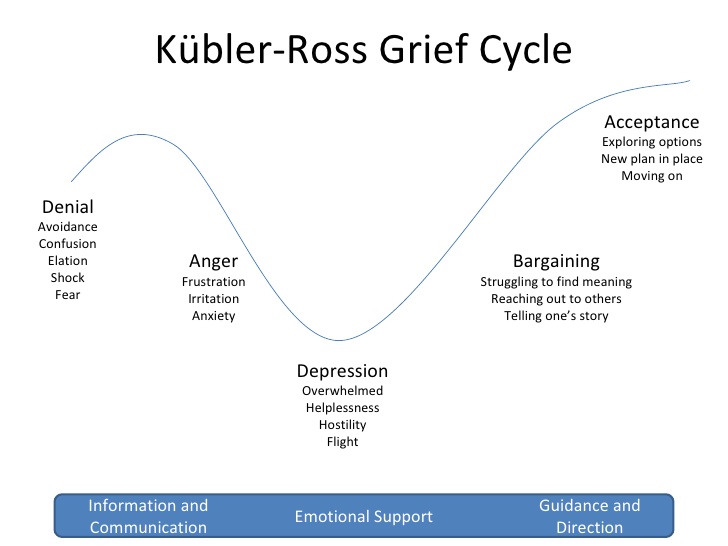

To make our characters’ grief feel believable, it seemed useful to explore how psychiatrists define its stages in real life. The classic model comes from Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, a Swiss-American psychiatrist who identified five key stages in her 1969 book On Death and Dying.

The Five Stages of Grief

When we are in shock after losing someone important in our lives, we may enter the first stage: denial. In this phase, we try to dissociate from what has happened to protect our feelings. There is only one step between “this can’t be happening” and “this isn’t fair,” a shift that can emerge from the frustration and anger we feel in the face of loss. In this second stage, we try to make sense of what happened; we may look for someone to blame, or feel at odds with the world, with God, or with ourselves for not having prevented it.

The third and fourth stages are closely intertwined. The bargaining stage is when we wonder whether we did everything we could to prevent the loss, followed by the stage of sadness and emptiness, which brings us into direct contact with our feelings for the person who is gone. This fourth stage is most commonly associated with grief, and while it is natural, it can slip into a depressive state.

The third and fourth stages are closely intertwined. The bargaining stage is when we wonder whether we did everything we could to prevent the loss, followed by the stage of sadness and emptiness, which brings us into direct contact with our feelings for the person who is gone. This fourth stage is most commonly associated with grief, and while it is natural, it can slip into a depressive state.

The final stage —and here I return to Dr. Rojas’s quote— is acceptance. From a narrative point of view, this can be one of the richest stages to explore, because our characters must learn to live with the loss and adapt to their new reality.

Modern psychologists emphasize that people don’t always experience all five stages, nor do they necessarily move through them in this order. Most of us —and, by extension, our characters— oscillate between moments of pain and moments of acceptance.

Tools and Tips for Storytellers

As a mirror of real life, film and literature portray grief convincingly when they show the emotional arc that spans from denial and sorrow to acceptance and transformation. To help sketch that emotional journey, here are several tips accompanied by specific examples.

Show, don’t tell the shock. Early on, characters may behave as though they haven’t fully processed the loss. They may perform small gestures aimed at the absent person as if they were still alive, such as setting them a plate at the table or leaving them a voice message. In her autobiographical essay The Year of Magical Thinking (2005), Joan Didion responds to her husband’s sudden death by keeping his clothes and shoes, hoping he might return. Getting rid of them would mean acknowledging the irreversible.

Introduce external and internal tensions. Narrative tension can arise from conflicts that surface alongside predictable feelings of sadness and pain. Your character may become irritable with people who try to help or offer sympathy, or feel anger toward themselves, toward God, or toward the cause of the loss. In Kenneth Lonergan’s superb Manchester by the Sea (2016), Lee Chandler (Casey Affleck) navigates devastating grief after the death of his children. His pain is wrapped in self-destructive anger, and he is unable to accept comfort from those around him. Every interaction with his ex-wife, his nephew, or the townspeople becomes dramatic friction. Here, grief is an ongoing internal struggle that clashes with the help others try to offer.

Let the character hit bottom. As the emotional climax of grief, your character may experience a moment of deep disconnection from the world —losing appetite, sleep, motivation, or in more extreme cases, falling into addiction or contemplating suicide. In Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2006), the father, after his wife’s death, sinks into a nearly overwhelming sadness and repeatedly considers suicide. The novel is an exploration of grief pushed to its limits in an extreme, apocalyptic environment.

Create a spark of transformation. As sadness begins to shift into acceptance, include a small moment in which your character starts learning to live with the absence. This spark might come in the form of a conversation, a gesture of self-care, or a return to routine. Acceptance should not be portrayed as “being fine,” but rather as a way of moving forward despite the pain. In Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close (2005), Oskar begins living with his father’s absence when he and his mother finally speak openly about what they’ve both been hiding; that conversation breaks the bubble of trauma and sets him on the path toward acceptance.

End with meaningful adaptation. Rather than an epic or revelatory moment, the narrative should arrive at a new stability born from the wound, where the protagonist integrates aspects of the loss into their identity. A character might make a decision aligned with their new reality —moving to a new place, choosing a new career path— or transforming their bond with what they lost into something different, like a ritual or a lesson. In Nomadland (2020), Fern, the protagonist played by Frances McDormand, chooses a nomadic life not as an escape but as a way to honor her husband’s memory. Her meaningful adaptation lies in accepting that “home” is no longer a fixed place, but a new way of living.

Throughout this emotional arc, remember that many narrative tools can enrich your story: funerals, photographs, scents, letters, or flashbacks to conversations can all help portray different phases of grief. Other elements that add authenticity include setbacks —moments when the character seems to move forward but then slips back— and temporal markers like the seasons or changes in light that reflect internal evolution. While grief can easily fall into cliché or melodrama, the right approach can lead to powerful, moving stories.

The third and fourth stages are closely intertwined. The bargaining stage is when we wonder whether we did everything we could to prevent the loss, followed by the stage of sadness and emptiness, which brings us into direct contact with our feelings for the person who is gone. This fourth stage is most commonly associated with grief, and while it is natural, it can slip into a depressive state.

The third and fourth stages are closely intertwined. The bargaining stage is when we wonder whether we did everything we could to prevent the loss, followed by the stage of sadness and emptiness, which brings us into direct contact with our feelings for the person who is gone. This fourth stage is most commonly associated with grief, and while it is natural, it can slip into a depressive state.

Comentarios